A study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine links persistent pain with progressive cognitive decline and dementia. But the mechanism is quite unclear. There are actually a few possibilities, as F. Perry Wilson, MD, discusses in this 150-second analysis.

Chronic pain is an epidemic in the U.S., but this study appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine suggests that the consequences of chronic pain may extend beyond quality-of-life issues.

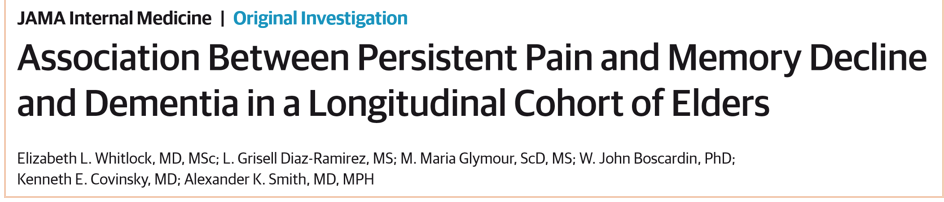

Researchers led by Elizabeth Whitlock at UCSF examined data from the Health and Retirement Study, a longitudinal survey study of just over 10,000 older adults. Every two years, the participants provided answers to questions about pain and cognition, along with a host of other factors.

They divided that group into the 1,120 individuals who reported moderate to severe pain in both the 1998 and 2000 surveys, and everyone else.

As you can see here, these folks were quite different at baseline. People with persistent pain were less likely to be male, were less educated, less financially secure, and had a greater burden of comorbidities, especially depression.

But the question was whether the people with pain would have a more rapid decline in cognitive function, or a higher risk of dementia. I think the risk-of-dementia analysis is the most salient here.

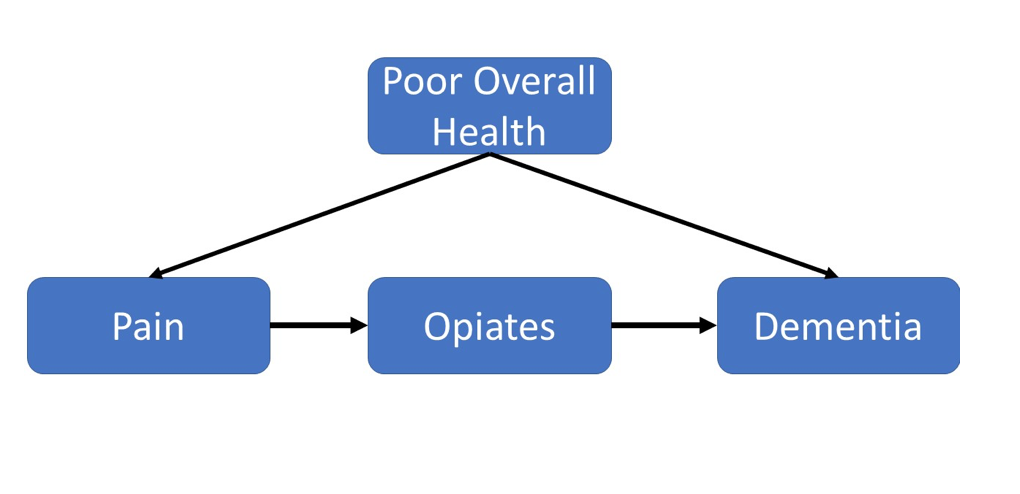

Start with the graph on the left. The x-axis shows us time in years from the year 2000 visit. The y-axis shows us the predicted dementia probability. Now, why not just show us the rate of dementia? Well, the researchers didn't have access to that data – this was just a survey. So they used a technique to convert the survey answers to a predicted dementia risk. In other words, for each person they could hang up the phone, enter the data into a model, and say – huh – that guy has a 50% chance of being demented. No, it's not perfect, but it's not bad.

In any case, the left box shows us the unadjusted risk. People with persistent pain are clearly at higher risk of dementia over time. But when you account for all those baseline differences, as they do in the graph on the right, those risks get majorly attenuated.

And this gets us to an interesting issue. We have a few ways to interpret this.

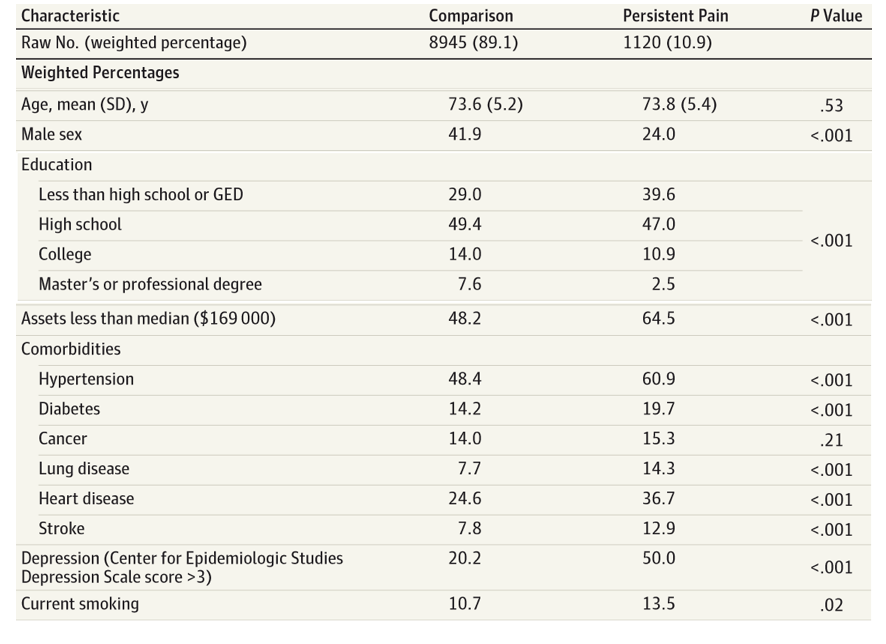

One possibility is that pain really does damage the brain. It's not so far-fetched.

Persistent pain may lead to significant cortisol elevation which can certainly alter brain chemistry. If you buy that, you'd expect that aggressive treatment of pain in the elderly, perhaps even with opiates, will reduce the risk of dementia.

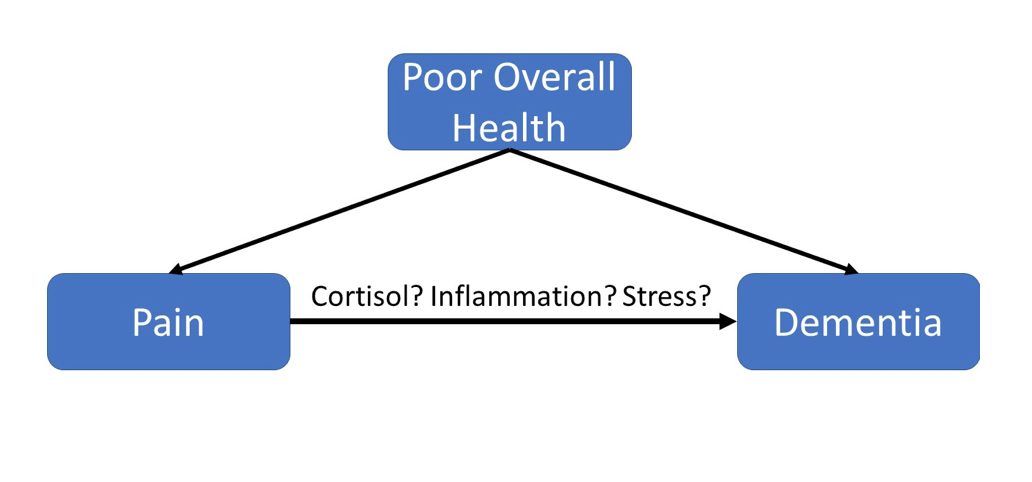

But there's another possibility. Maybe it was the treatment of the persistent pain in this group that caused the cognitive decline.

We have no details with regards to how the individuals with pain were being treated. If some of them were receiving opiates, is it crazy to think that opiates were causing their brains to run a bit slower?

But here's my version of Occam's razor for medical studies: given multiple interpretations of the data, the least interesting tends to be correct. In this case, I think pain is most likely just a proxy for poor overall health status and neither treatment of pain nor avoidance of treatment of pain will do much to alter the rate of dementia in this population.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an assistant professor of medicine at the Yale School of Medicine. He is a MedPage Today reviewer, and in addition to his video analyses, he authors a blog, The Methods Man. You can follow @methodsmanmd on Twitter.