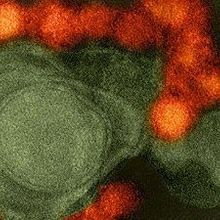

WIKIMEDIA, NIAIDWhen the immune system has eliminated the last traces of Zika virus from the blood, low-level infection may continue at certain sites around the body. A study published in Cell today (April 27) reveals that the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is one such sanctuary, which, if also true for infected humans, may have implications for long-term neurological health.

WIKIMEDIA, NIAIDWhen the immune system has eliminated the last traces of Zika virus from the blood, low-level infection may continue at certain sites around the body. A study published in Cell today (April 27) reveals that the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is one such sanctuary, which, if also true for infected humans, may have implications for long-term neurological health.

“Up until now, everyone was focused on the acute [infection]—what happens when a person gets infected initially by a mosquito bite. But what this paper tells us is that maybe, two months down the line, symptoms could manifest from this later stage of virus replication in the central nervous system and other sites,” said microbiologist and immunologist Andres Pekosz of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore who was not involved in the research. “Right now, we may be missing some of the disease associated with infection because...

Zika virus infection generally causes a short acute illness of fever, fatigue, headache and other mild symptoms, or can be entirely asymptomatic. But, in pregnant women, infection can cause grievous fetal abnormalities, including microcephaly. In rare cases, Zika can also induce Guillain-Barré syndrome and other neurological symptoms in adults.

Although the symptomatic phase of an infection may last just a week or so, recent evidence suggests that in some people the virus can stick around long-term. Zika virus has been detected in the semen of infected men long after the febrile illness has faded, for example, as well as in fetal brain and placental tissues from pregnant women.

“There is clear evidence from humans that Zika virus does persist in certain anatomic sanctuaries,” said Harvard Medical School’s Dan Barouch who, along with colleagues, has now pinpointed some of these hideouts in monkeys.

Barouch’s team injected Zika virus into rhesus monkeys—which exhibit similar symptoms and disease progression to that seen in humans—and examined an array of tissues at different time points during and after acute disease. The researchers found that while there was a clearance of virus from day seven to 10 in the peripheral blood, which “tightly correlated with the rapid emergence of virus-specific neutralizing antibodies,” said Barouch, the virus remained in the CSF for up to 42 days and in the lymph nodes and colorectal mucosa for up to 72 days.

Because of the blood-brain barrier, “the virus-specific antibodies are not found in the central nervous system,” said Barouch, adding that this might partly explain the retention of virus in the CSF. But a lack of antibody access cannot be the whole story, he said, because it does not explain retention of the virus in the gut lining and lymph nodes, where antibody access would be unhindered.

To better understand the molecular correlates of viral persistence, the researchers examined gene expression data from CSF and lymph nodes during initial and prolonged infection. They found that viral persistence correlated with the upregulation of genes involved in pro-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic pathways, as well as in signaling via mTOR—a kinase that regulates numerous cellular processes and that, notably, has been shown to cause microcephaly and neurodegeneration when overexpressed in embryonic and adult mice.

The fact that mTOR has “previously been shown to be associated with neurological problems” in mice, said Barouch, “is very intriguing.”

Going forward, “the question is going to be, what does this [persistent infection] mean,” said Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who was not involved in the research. “As exciting as it is to get new information, it also raises questions,” Fauci continued. Among them, “if the virus can linger in the central nervous system even after people apparently recover, will we start seeing some subtle effects later on, or is it just going to be a phenomenon that is inconsequential clinically? Right now we don’t know the answer to that because we don’t have enough experience with long-term effects of Zika.”

M. Aid et al., “Zika virus persistence in the central nervous system and lymph nodes of rhesus monkeys,” Cell, 169: 1–11, 2017.

Interested in reading more?